“Do we design the architecture and the buildings shape us?” or “Was it penicillin that saved the day?”

.

“We have arrived at a new juncture of disease and architecture, where fear of contamination controls what kinds of spaces we want to be in.”

How the Coronavirus is reshaping how we design our spaces – Vision Group for Sidmouth

.

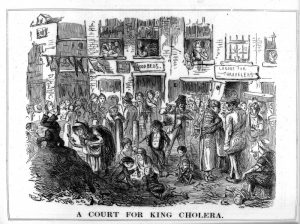

This could equally be said about other periods, when the importance of designing for good health was being understood – for example, during the cholera crisis in London in the 1830s and 40s:

This could equally be said about other periods, when the importance of designing for good health was being understood – for example, during the cholera crisis in London in the 1830s and 40s:

Cholera in Victorian London | Science Museum

.

The medical profession has long recognised the importance of light and air for health – as this account on Graham Cooper’s website shows, from his book “Art and Nature: Healing”:

Right to Daylight | grahamcooper.com

.

A correspondent asks:

I wonder how this pandemic will effect East Devon and Sidmouth planning (eg the new Local Plan) and building regulations at a local level.

(For example, the new EDDC HQ open plan vs Knowle’s closed asbestos-contaminated spaces!)

It reminds me of the Cholera epidemic and newly established public health concerns which led to modern international architecture. It was thought the stench “miasma” carried the disease, so the pavilion wards hospitals encouraged ventilation and large windows. In the end, it wasn’t so much miasma but the u-bend WC sanitation which helped to resolve the problem, but the efficient open-plan pavilion was continued for the next 100 or so years.

Maybe it is a case of – Do we design the architecture and the buildings shape us? or Was it penicillin that saved the day?.

I think 19th Century viruses and social distancing has raised all sorts of worrying public v private concerns.

Can the architecture be the answer or is it a case of vaccinations, testing and tracing?

.

Finally, we now know that living in over-cramped housing with little access to open spaces not only produces much more unhealthy environments in general – but that this is a determining factor in survival rates from the coronavirus:

Global Urban Inequalities During COVID-19 | World Resources Institute

‘Bad housing kills’: How coronavirus overwhelmed the UK’s most overcrowded community | The Independent A look at overcrowding, mainly in London.

.

This piece from today’s Conversation puts things into further historical context, although a little simplistically:

.

We’ve known for over a century that our environment shapes our health, so why are we still blaming unhealthy lifestyles?

We’re healthier and live longer than our ancestors, yet we’re constantly reminded of deaths caused by war, terrorism and natural disasters. As terrible as these events are, they accounted for less than 1% of the 56 million worldwide deaths in 2017.

Another colossal distraction is the focus on lifestyle as a way to better people’s health and reduce health inequalities. Of course, what people eat, how much they exercise, whether they smoke and how much alcohol they drink have a bearing on their health. But what matters much more is the circumstances in which people are born, live, work and age – the “social determinants” of health.

The fact that the environment shapes people’s lives and health has been known for a long time. In 1842, Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain highlighted how the ill health of the poor was not the result of their idleness but of their terrible living conditions.

In his semi-autobiographical novel The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, written over a century ago, Robert Tressell explained how the poor health of the hero of the book, impoverished painter and decorator Frank Owen, could not be solved by medicine alone. It was social medicine that he needed: “The medicine they prescribed [Frank Owen] and which he had to buy did him no good, for the truth was that it was not medicine that he – like thousands of others – needed, but proper conditions of life and proper food.”

And over 70 years ago, Sir William Beveridge, the architect of the British welfare state, called for action to tackle the root causes of poor health: poverty, low education, unemployment, poor housing and other public health issues, such as malnutrition and inadequate healthcare.

There is no denying that great progress has been made since the work of Chadwick, Tressell and Beveridge. Far fewer people in the UK experience the absolute poverty, squalor and overcrowding they described. But the fact remains: the profound health inequalities between rich and poor that have been highlighted throughout the past century – most notably in the Black Report, which was published 40 years ago – remain today. In 2020, a baby boy born in wealthy Kensington, London, can expect to live over ten years longer – and nearly 20 more years in good health – than a baby boy born in relatively deprived Kensington, Liverpool.

.

So, perhaps it is a case of “We design the architecture and the buildings shape us”, rather than “It was penicillin that saved the day”.