How should we be talking about the environment?

.

By now it’s become very clear that the perils of greenwashing have spread far and wide – and need watching if not regulating. And this is what has just happened, as the FCA introduces new anti-greenwashing measures:

A new rule intended to prevent greenwashing has now come into force. The anti-greenwashing rule was announced by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) last year and came into force on 31 May 2024. The anti-greenwashing rule is the first in a series of measures announced by the FCA to formalise sustainability disclosure requirements in the UK... The anti-greenwashing rule was established after concerns that companies were making false sustainability related claims about financial products that they were offering.

The only problem is that this action, together with greater public awareness, might work too well, as the FCA’s anti-greenwashing rules should have ‘substantial impact’.

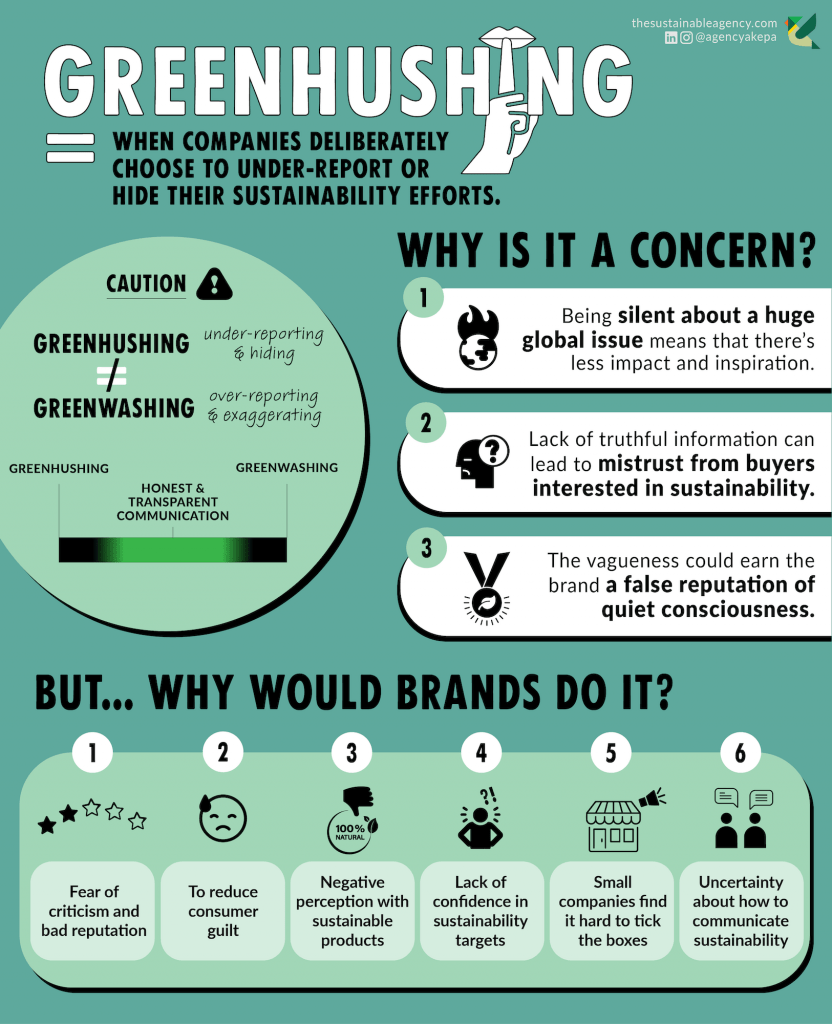

And so we are now seeing ‘green hushing’ on the rise, as companies keep climate plans from scrutiny.

BBC Radio 4’s series Rare Earth on the environment has returned and in today’s first episode looks at just this, urging us to Hush! Don’t Mention the Environment:

In the first edition of a new series of Rare Earth Tom Heap and Helen Czerski reveal a new phenomenon- ‘Greenhushing’. Big corporations that once trumpeted their green credentials are now staying very quiet about the environment. From the left they’ve been attacked by green zealots eager to expose greenwashing, when their claims don’t stand up to scrutiny. Meanwhile from the right any hint of environmental action is condemned as ‘woke’. Better, some business advisors believe, to keep quiet about the issue and avoid offending any of their potential customers or falling foul of new regulations.

Tom and Helen discover how hotel towels inspired the coining of the term greenwash, by ecologist Jay Westerveld. Moving on to greenhushing, they’re joined by business experts and PR gurus to consider the broader impact of business and industry disengaging from the core issue of our time. Solutionist Solitaire Townsend explains why she thinks some greenhushing is a good thing. Tom and Helen take a deep dive into what might be driving greenhushing with the former CEO of French food giant Danone, and now head of the International Sustainability Standards Board, Emmanuel Faber, international trade and sustainability expert Dr Rebecca Harding, and journalist turned PR advisor Piers Scholfield.

And coincidentally, the latest edition of The Conversation’s ‘Imagine’ newsletter [what researchers think of a world with climate action] considers pretty much the same:

Why we can’t vote climate change out

The world’s biggest election took place in heat so severe it claimed the lives of several poll workers. Nearly one billion people were eligible to vote in the election that returned Narendra Modi to power in India, but many will have risked their health in doing so. India has just suffered the harshest heatwave of its history. For voters in the 64 countries with elections this year (comprising half of adults globally), the climate crisis is likely to loom large.

Let’s imagine a political response that is equal to the climate crisis. Joëlle Gergis, a climate scientist at the University of Queensland, explains what it would have to contend with.

The polls are melting

Like many of her colleagues, Gergis has been struck by how bleak the latest climate science assessments are. “We need you to stare into the abyss with us and not turn away,” she says. After decades of consciously inflaming the climate crisis – by continuing to burn more and more fossil fuel and destroying Earth’s natural carbon sponges, forests and wetlands – humanity has reached a stark juncture, she says: “Even if nations make good on their net zero promises – which is a big ‘if’ because right now many nations’ pledges have no finance, weak implementation or limited political ambition, so are effectively empty promises – there is a 90% chance that we are still on track for 2.4°C of global warming under this best-case scenario, which will lock in centuries of irreversible changes to the climate system.”

For an idea of how bad this optimistic outcome is, consider that 1.5°C is the internationally agreed “safe” limit for long-term warming. Earth marked its first year-long breach of this temperature threshold in February.

Nature doesn’t get a vote and isn’t waiting for human institutions to provide relief writes Jonathan Goldenberg, an evolutionary biologist at Lund University. Right now, North American migratory birds are evolving smaller bodies and longer wings to give themselves a slim advantage in increasingly brutal heatwaves. These adaptations, Goldenberg explains, make it easier for them to dissipate heat. Reptiles and amphibians – so-called ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals (though their blood isn’t actually cold, Goldenberg says, they just rely on their environment to heat up and cool down rather than their metabolism like we do) – are less fortunate. Unable to directly regulate their internal temperature, lizards in central South Africa are responding to climate change in a way that may seem eerily familiar: by aiming to do as little as possible, and so avoid overheating. “That probably means less time foraging and mating, potentially stunting their growth and reproduction,” Goldenberg says.

A potentially lethal inertia has gripped this species and our own. That’s not to say there aren’t regular votes on the outcome of Earth’s climate this century. There are, they just tend to be in boardrooms.

“Take the case of Shell, whose shareholders recently voted to decelerate the UK-based oil giant’s climate targets,” says Stefan Andreasson, a reader in comparative politics at Queen’s University Belfast. “Shell had planned to cut its ‘net carbon intensity’ by 20% by 2030 and 45% by 2035, but now seeks a 15%-to-20% reduction by 2030 and no longer has a 2035 target. One important explanation for [this shift] is that world demand for fossil fuels keeps rising”, Andreasson adds.

Who voted for this?

How is it that the profit expectations of businesses can supersede the public desire for a stable climate in a supposed democracy? It’s not by accident argues Eve Darian-Smith, a professor of global and international studies at the University of California, Irvine. “Around the world, many countries are becoming less democratic. This backsliding on democracy and ‘creeping authoritarianism,’ as the US State Department puts it, is often supported by the same industries that are escalating climate change,” she says.

The notion of democratically elected leaders as protectors of the public’s interests, securing common goods like clean air and water, has been aggressively undermined in recent years. Darian-Smith traced the influence of campaign spending in her native US and found not only that the better-funded candidates tend to win, but that donations to Republican candidates from sources linked to the oil and gas industry have more than doubled since 2010. “The energy industry has in effect captured the democratic political process and prevented enactment of effective climate policies,” she says.

Is the lesson that we must suspend democracy to fix the climate? Quite the opposite according to Rebecca Willis, a professor in energy & climate governance at Lancaster University. “To tackle the climate crisis, we need more, and better, democracy, not less,” she says. “The more we find out about how to build a public mandate for climate action, and the more we include people in genuine debate and deliberation, the more likely we are to find a way through the climate crisis.”

Finally, here’s an overview of What Greenhushing is from the sustainability agency Akepa – followed by their advice to clients:

So how can brands avoid greenhushing?

The reasons for all this circumspection are understandable. But greenhushing is not the solution. The inevitable consequence of greenhushing will be a lack of corporate sustainability. It would be a pity if the fear of criticism was the leading reason that financial, intellectual, and emotional investment in sustainability started to diminish. With all the hype around greenwashing, brands should instead take a more positive approach:

- Be transparent. Little steps are appreciated, if customers can see that actions within a company are genuine and not contradicting. For example, if you’re a small business, don’t worry about not having enough means for a big certification like B Corp. There are other ways to show true sustainability off: try a behind-the-scenes, be transparent about your supply chain, or show how your business is circular.

- Admit imperfection. Some brands deserve criticism. But others should be confident enough to talk the walk if there aren’t any fair reasons for major backlash, while also admitting imperfection. Yearly sustainability reports that admit faults and describe meaningful improvements can help.

- Let the laws do the talking. Stricter laws against greenwashing are coming but they should only punish those who are actually greenwashing. If that’s not you, then don’t be stricken by panic and retreat into a shell.

- Choose your partners carefully. A good agency, for example, should know how to communicate sustainability and avoid the pitfalls of either greenwashing or greenhushing. Quite a few of the most egregious greenwashing cases have been committed by clumsy marketing teams that don’t know the area.

Perhaps there is also a lesson for the people looking on too. If we do want a more sustainable world then we need to understand that sustainability can’t happen overnight. A transition needs to happen from a far from perfect place.

Of course it’s still important to call out greenwashing brands but not all brands deserve to be scolded. It’s a fine line, and we need to tread it carefully. We just hope that greenhushing won’t interrupt those with grand plans over the coming years.

…