Farmers and farmworkers should be paid more for their efforts.

But both producers and consumers should value the ‘true costs’ of food production.

.

We don’t have enough people who want to work on the land – and with the pool of foreign workers drying up, we are facing a real dilemma – but it’s been a problem brewing for some time now:

How to plug the migrant labour gap in farming

.

It’s been very difficult to recruit locals to do farm work – but not because they are ‘lazy’:

‘Just not true’ we’re too lazy for farm work, say frustrated UK applicants | theguardian.com

.

A major issue is that much farm work is seasonal – and for that you need a burst of work from a dedicated workforce – which is not attractive to anyone looking for a long-term, permanent job.

.

It’s now ten years ago since this issue was considered in a provocative BBC documentary:

The Day the Immigrants Left | bbc.co.uk

Unemployed take on immigrants’ jobs for Evan Davis documentary | theguardian.com

Evan Davis on what would happen if all immigrant workers left … | telegraph.co.uk

The day immigrants left 2010 FULL | youtube.com

.

If we want people to pick crops or even grow their own to sell, then working on a farm does need to become more attractive – and that includes better conditions and better pay.

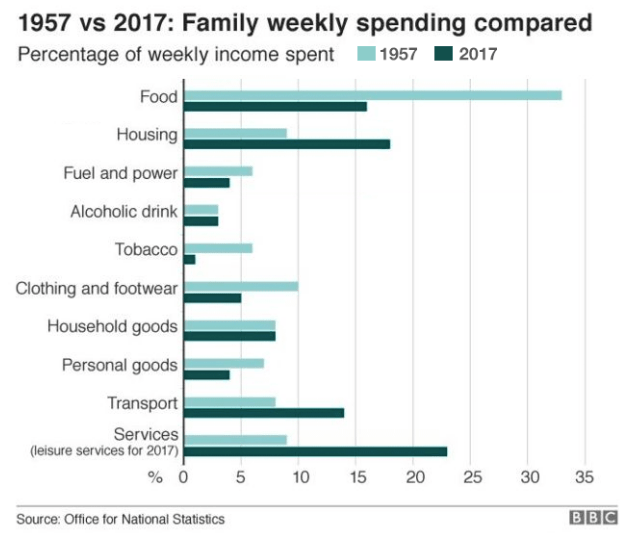

But, as noted in a recent post from East Devon Watch, the pay is not attractive because we are not prepared to pay for our food. Perhaps if we paid less for housing proportionately, as this graph from the BBC shows:

.

.

Why the UK has such cheap food | bbc.co.uk

.

But if we are to produce more food locally, we will need to address these questions:

Local food: local resilience to global risk

Local community support through food

How is food produced and where?

.

A piece from Nature last week looked at the issue of cheap food and measuring value:

.

The true cost of food

Prices that better reflect the environmental costs of food can promote more sustainable production and consumption practices.

Most environmental impacts of food production and consumption are not economically valued and are not, therefore, felt ‘in the pocket’. They are what economists call hidden costs — the difference between the market price of food and its comprehensive cost to society.

Not balancing the books with regard to the true cost of food propagates failures within the food system, the most pressing of which are poor production practices and the promotion of a convenience and throwaway culture that encourages waste, aggravates pollution and further dissociates consumption from production. This is even more problematic in a world of severe socioeconomic disparities, where the consequences of excessive production and consumption patterns are felt by everyone, both across and within countries.

However, an effort to price food based on the principle of true cost could help minimize the mismatch between who causes pollution and who pays for it. By reflecting, at least in part, the environmental impact of food, true pricing could promote more sustainable means of production, signalling to consumers the footprint of different food items and encouraging them to make choices in line with Sustainable Development Goal 12 on responsible production and consumption.

In fact, those at the end of the supply chain are arguably in the best position to drive positive change along its entirety — from retailers to distributors, processers and right back to the farm — although they should not bear the cost alone…

The true cost of food | nature.com

.

And if we’re going to have to pay more for our food, then we need to address the issue of low pay across the board – and not just for farmworkers:

.

One-third of key workers earn £10 an hour or less, study finds

One-third of key workers earn £10 an hour or less, with food and social care employees paid the lowest paid, according to a new study. Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) suggests that the hourly wages of key workers are 8 percent lower on average than other workers.