A large share of China’s emissions is from the production of goods consumed in rich countries.

Meanwhile:

“Emissions in China are down because the economy has stopped and people are dying, and because poor people are not able to get medicine and food. This is not an analogy for how we want to decrease emissions from climate change.”

.

There is something called ‘carbon inequality’:

The majority of the world’s richest 10% high emitters still live in OECD countries; around a third are from the US. While the total emissions produced in China divided on a per capita basis have now surpassed those of the European Union, the per capita lifestyle consumption emissions of even the richest 10% of Chinese citizens are still likely to be considerably lower than the richest of their OECD counterparts.

This is because such a large share of China’s emissions is from the production of goods consumed in rich countries.

EXTREME CARBON INEQUALITY | cdn.oxfam.org

.

In other words, we have been outsourcing our CO2 emissions:

Britain merely ‘outsourcing’ carbon emissions to China, say MPs | the guardian.com

.

But it’s a complicated thing to work out:

.

As this piece back in 2017 showed:

.

A closer look at how rich countries “outsource” their CO2 emissions to poorer ones

In China, roughly 87 percent of the steel and 99 percent of the cement produced is consumed domestically. The vast bulk of the country’s climate pollution isn’t being driven by foreigners; it’s being driven by domestic growth.

In fact, one notable trend in China is the outsourcing of emissions within the country’s own borders. A 2013 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that China’s richer coastal provinces tended to consume a lot of goods made in the poorer inland provinces. “China is treating its own hinterland just the way the whole world treats China,” Klaus Hubacek, a co-author of the paper, told the BBC.

But as Glen Peters, a scientist at the CICERO Center for International Climate Research and a key figure at the Global Carbon Project, pointed out in a recent post with a few of his colleagues, the actual policy implications of these sorts of environmental flows rarely get discussed.

One big question, they write, is whether this sort of outsourcing should be taken more seriously in international climate negotiations. Under the Paris climate deal, countries are generally held accountable for the emissions produced within their own borders. But is that fair? Should the US or Europe take at least some responsibility for the pollution produced overseas to make the goods they enjoy? So far, this idea hasn’t gained much traction, in part because CO2 outsourcing has been so tricky to measure precisely. But, Peters and his colleagues note, we may want to revise that view as we gain a better understanding of each country’s true “environmental footprint.”

A closer look at how rich countries “outsource” their CO2 emissions to poorer ones | vox.com

.

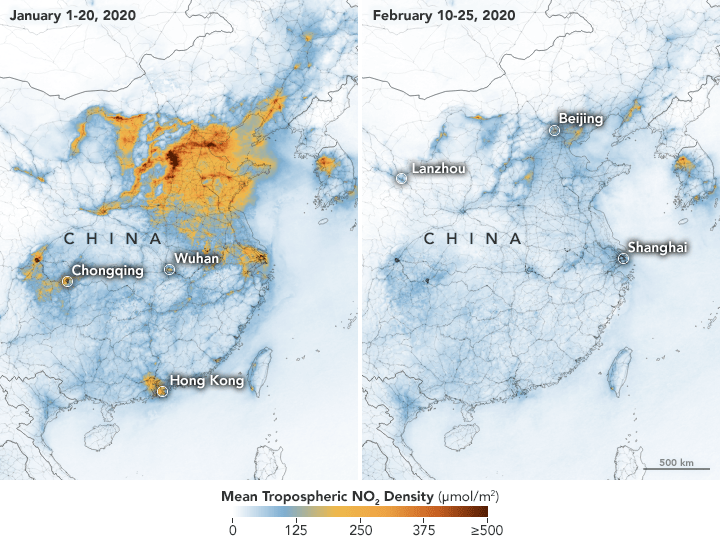

Suddenly, China’s skies are clearing, simply because China is producing less stuff to export:

.

.

.

Airborne Nitrogen Dioxide Plummets Over China | earthobservatory.nasa.gov

NASA confirms a fall in greenhouse gas emissions in China amid coronavirus outbreak | euronews.com

Maps show drastic drop in China’s air pollution after coronavirus quarantine | theverge.com

.

It’s complicated:

.

How the Coronavirus Pandemic Is Affecting CO2 Emissions

“There’s been a lot of studies on the benefits of telecommuting, and the conclusion usually is ’it depends,’” Jones said. If people are spending more time in their homes, they could be using more energy. It depends largely on weather conditions, geography and different family lifestyles.

“If you come home to a cold house and you have to heat it, that’s going to more than offset the savings from not driving your vehicle to work, on average,” Jones said. “If you come home to a beautiful day like we have in California, and there was somebody home anyway, really we’re not using much more energy than if I were at work.”

There’s also the possibility that people may spend more time watching television or using appliances if they’re cooped up in their houses, noted Jacqueline Klopp, co-director of the Center for Sustainable Urban Development at Columbia University. “That could end up having a higher energy use,” she said.

Pandemics like COVID-19 could also spur less obvious behavior changes, which may nonetheless affect a household’s carbon footprint.

For instance, reports have suggested a recent spike in online shopping and home deliveries, especially for groceries. This is likely another byproduct of the virus as people increasingly avoid public spaces.

The carbon footprint of online shopping, compared with making purchases in a store, is often tricky to parse out. According to at least one recent study, it may largely depend on whether the deliveries come from a store in the community or are shipped in from somewhere else, and what means of transport the shopper would ordinarily use to pick up the goods in person.

That adds one more level of complexity to the impact of COVID-19 on household carbon footprints.

…

How the Coronavirus Pandemic Is Affecting CO2 Emissions | scientificamerican.com

.

Finally, it largely depends on what happens after:

.

Emissions are down thanks to coronavirus, but that’s bad

A month ago, CEOs couldn’t stop talking about their sustainability plans and green investments and activists were gloating about a global movement for Green Deals. Today, the European Union is postponing climate law debates, the Fridays for Future protests are heading online, and carbon-intensive industries from aviation to oil are looking for bailouts.

Any recession is unlikely to be a local blip. That’s because the factors driving the initial economic downturn are global, severe and hitting supply-and-demand at the same time. While that might cut emissions in the short-term, that’s little cause for joy. Gernot Wagner, a clinical associate professor at New York University’s Department of Environmental Studies, told MIT Technology Review: “Emissions in China are down because the economy has stopped and people are dying, and because poor people are not able to get medicine and food. This is not an analogy for how we want to decrease emissions from climate change.”

It’s after any recession that the real problems can start for climate advocates. Helen Mountford of the World Resources Institute said that post-recession economies can see a surge in emissions: “After the global financial crisis of 2008, for example, global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production grew 5.9 percent in 2010, more than offsetting the 1.4 percent decrease in 2009.” This time, she hopes “low-carbon and resilient infrastructure” would be a priority in any stimulus package to avoid an uptick in emissions as economies recover.

Here are factors that could help and hurt the climate, in both the short and longer terms:

…

Emissions are down thanks to coronavirus, but that’s bad | politico.com