A radical practice is suddenly getting mainstream attention. Will it change how we help one another?

“It’s fantastic to see so many people engaging with this, including a huge number who have never considered self-organised working before.”

.

Around these parts, there is a lot of ‘mutual aid’ happening:

.

As is elsewhere around the country:

COVID-19 Mutual Aid & Community Response Groups | manchestercommunitycentral.org

Mutual Aid UK Groups | healthwatchnorthyorkshire.co.uk

Community support – mutual aid | cheltenham.gov.uk

Mutual aid network responds to coronavirus crisis | rochesterbeacon.com

.

And elsewhere around the world:

Mutual-aid networks fill in the gaps | coloradopolitics.com

COVID-19 MUTUAL AID & ADVOCACY | facebook.com/cityrepair

Mutual Aid and Solidarity in Iran during the COVID-19 Pandemic | merip.org

MTL COVID-19 Mutual Aid Mobilisation d’entraide | facebook.com

Russia’s Chinese community weathers epidemic with mutual aid, joint efforts | globaltimes.cn

.

Even in China:

.

The social support networks stepping up in coronavirus-stricken China

Below the sweeping centralized measures, decentralized networks have provided relief to thousands.

During this time, new forms of organizational collaboration, from governmental agencies and businesses to media, from NGOs and first-aid groups to alumni networks and self-organized volunteer groups, began emerging. Volunteering has been widely practiced in China, and this time it has seen a boost from new organizational forms. The whole society self-mobilized in a way never seen before, forming social networks of support. Some offer relief and support to the frontline, some facilitate the needs of overlooked groups such as pregnant women, migrant workers, people with chronic diseases in virus-stricken regions, and others focus on keeping daily life running in other parts of China. What follows are observations on some of these social networks across scales and combining agency horizontally and vertically, all with a human touch…

The social support networks stepping up in coronavirus-stricken China | opendemocracy.net

.

Here’s a definition of sorts:

Here’s a definition of sorts:

Mutual aid (organization theory) | en.wikipedia.org

.

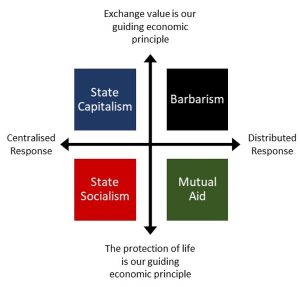

And these news pages looked at “a number of possible futures, all dependent on how governments and society respond to coronavirus and its economic aftermath”:

Building a future: looking beyond the crisis

Which included ‘mutual aid’:

What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possible futures | theconversation.com

.

As the New Yorker points out, the term ‘mutual aid’ is now everywhere – and shows that it’s an idea that cannot be easily defined on the traditional political spectrum:

.

What Mutual Aid Can Do During a Pandemic

A radical practice is suddenly getting mainstream attention. Will it change how we help one another?

As the press reported on this immediate outpouring of self-organized voluntarism, the term applied to these efforts, again and again, was “mutual aid,” which has entered the lexicon of the coronavirus era alongside “social distancing” and “flatten the curve.” It’s not a new term, or a new idea, but it has generally existed outside the mainstream. Informal child-care collectives, transgender support groups, and other ad-hoc organizations operate without the top-down leadership or philanthropic funding that most charities depend on. There is no comprehensive directory of such groups, most of which do not seek or receive much attention. But, suddenly, they seemed to be everywhere…

A decade ago, the writer Rebecca Solnit published the book “A Paradise Built in Hell,” which argues that during collective disasters the “suspension of the usual order and the failure of most systems” spur widespread acts of altruism—and these improvisations, Solnit suggests, can lead to lasting civic change. Among the examples Solnit cites are tenant groups that formed in Mexico City after a devastating earthquake, in 1985, and later played a role in the city’s transition to a democratic government. Radicalizing moments accumulate; organizing and activism beget more organizing and activism…

Radicalism has been at the heart of mutual aid since it was introduced as a political idea. In 1902, the Russian naturalist and anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin—who was born a prince in 1842, got sent to prison in his early thirties for belonging to a banned intellectual society, and spent the next forty years as a writer in Europe—published the book “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.” Kropotkin identifies solidarity as an essential practice in the lives of swallows and marmots and primitive hunter-gatherers; coöperation, he argues, was what allowed people in medieval villages and nineteenth-century farming syndicates to survive. That inborn solidarity has been undermined, in his view, by the principle of private property and the work of state institutions. Even so, he maintains, mutual aid is “the necessary foundation of everyday life” in downtrodden communities, and “the best guarantee of a still loftier evolution of our race.”

Charitable organizations are typically governed hierarchically, with decisions informed by donors and board members. Mutual-aid projects tend to be shaped by volunteers and the recipients of services. Both mutual aid and charity address the effects of inequality, but mutual aid is aimed at root causes—at the structures that created inequality in the first place…

In her book “Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America,” the Harvard political scientist Nancy L. Rosenblum considers the American fondness for acts of neighborly aid and coöperation, both in ordinary times, as with the pioneer practice of barn raising, and in periods of crisis. In Rosenblum’s view, “there is little evidence that disaster generates an appetite for permanent, energetic civic engagement.” On the contrary, “when government and politics disappear from view as they do, we are left with the not-so-innocuous fantasy of ungoverned reciprocity as the best and fully adequate society.” She cites the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Rose Wilder Lane, who helped her mother craft classic narratives of neighborly kindness and became a libertarian who opposed the New Deal and viewed Social Security as a Ponzi scheme…

What Mutual Aid Can Do During a Pandemic | newyorker.com

.

Here’s the leftist publication Red Pepper looking at how the term is being defined:

.

The politics of Covid-19: the frictions and promises of mutual aid

Thousands of mutual aid groups have sprung up around the UK, grounded in different experiences and perspectives. Whose vision of community-serving work will win out?

Summed up as ‘a group of people organis[ing] to meet their own needs, outside of the formal frameworks of charities, NGOs and government,’ the term ‘mutual aid’ has roots in Peter Kropotkin’s early 20th century anarchist writings. It’s been used to describe historical and current indigenous societies, medieval trades guilds, the UK co-operative movement and a host of other networks based on reciprocity and voluntary membership.

Now, with Tory councillors as well as anarchist activists using the term, the significance of ‘mutual aid’ at a local level is massively varied. It’s officially gone mainstream, and in this new context there are (at least) two perspectives emerging, each informed by different ideas about the role of the state. These perspectives – consciously or not – are present in every decision about process and practice on the ground.

The politics of Covid-19: the frictions and promises of mutual aid | redpepper.org.uk

.

With more comment from the liberal/leftist press:

Building a better world through mutual aid | theguardian.com

A Different Kind of Anarchy in the U.K. | slate.com

Coping with Covid19 – Mutual Aid and Local Responses in a time of Coronavirus | arc2020.eu

.

But there’s interest across the spectrum:

These Local Heroes Are Protecting People Because the Government Won’t | vice.com

How to build mutual aid that will last after the Coronavirus pandemic | americanmagazine.com

NWA Mutual Aid: Fighting coronavirus with hillbilly hospitality | fayettevilleflyer.com

Pandemics: The State As Cure or Cause? | c4ss.org

From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State by David T. Beito | fee.org

.

To finish: a piece from the Daily Mail:

.

‘Let’s make kindness go viral’

Thousands of thoughtful Brits have taken to social media to offer help to vulnerable neighbours during the coronavirus outbreak – as authorities warn anyone feeling unwell should avoid older people. Offers of help poured in on social media sites including Facebook, Twitter and Reddit amid fears for the frail and elderly, who are at greatest risk of serious illness as a result of Covid-19.

Catherine Mayer, co-founder of the Women’s Equality Party, posted on Twitter urging fellow users to volunteer or ask for support by using the hashtag #HowCanIHelp. ‘All of us rely on others for help and the coming weeks will see carers and support networks impacted by coronavirus,’ she said. ‘Use #HowCanIHelp to ask or offer practical assistance.’

Elsewhere, an online movement to place volunteers with vulnerable residents has been growing at an extraordinary rate, with almost 400 ‘mutual aid’ groups being established across the UK in little over 24 hours.

The National Food Service (NFS), an organisation aimed at tackling food insecurity, is now stepping in to offer the volunteers safeguarding training to help with issues such as data protection.

Louise Delmege, director of NFS Bristol, said: ‘I’ve been amazed by the quick response of the mutual aid groups. These have sprung up so quickly and are already forming into well-organised and thoughtfully co-ordinated groups. It’s fantastic to see so many people engaging with this, including a huge number who have never considered self-organised working before.’