Separating and making use of our urine

.

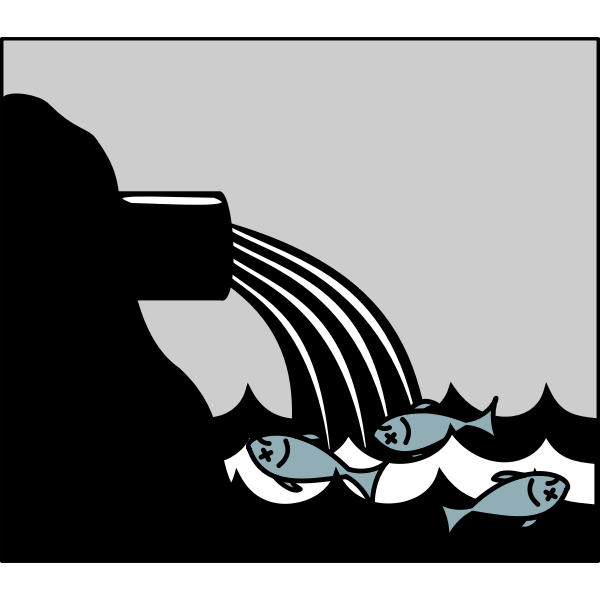

We have a problem with sewage:

Discharges of untreated sewage: SWW to answer questions – Vision Group for Sidmouth

They have a real problem in parts of Sweden – where they have come up with novel ways of dealing with it – or, rather, they’ve gone back to how we used to deal with human waste, as told by the latest from Nature:

The urine revolution: how recycling pee could help to save the world

Separating urine from the rest of sewage could mitigate some difficult environmental problems, but there are big obstacles to radically re-engineering one of the most basic aspects of life.

On Gotland, the largest island in Sweden, fresh water is scarce. At the same time, residents are battling dangerous amounts of pollution from agriculture and sewer systems that causes harmful algal blooms in the surrounding Baltic Sea. These can kill fish and make people ill.

To help solve this set of environmental challenges, the island is pinning its hopes on a single, unlikely substance that connects them: human urine.

Starting in 2021, a team of researchers began collaborating with a local company that rents out portable toilets. The goal is to collect more than 70,000 litres of urine over 3 years from waterless urinals and specialized toilets at several locations during the booming summer tourist season. The team is from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) in Uppsala, which has spun off a company called Sanitation360. Using a process that the researchers developed, they are drying the urine into concrete-like chunks that they hammer into a powder and press into fertilizer pellets that fit into standard farming equipment. A local farmer uses the fertilizer to grow barley that will go to a brewery to make ale — which, after consumption, could enter the cycle all over again.

The researchers aim to take urine reuse “beyond concept and into practice” on a large scale, says Prithvi Simha, a chemical-process engineer at the SLU and Sanitation360’s chief technology officer. The aim is to provide a model that regions around the world could follow. “The ambition is that everyone, everywhere, does this practice.”

The urine revolution: how recycling pee could help to save the world

Here’s a history of urine from the Smithsonian Magazine:

The saying goes that one person’s waste is another’s treasure. For those scientists who study urine the saying is quite literal – pee is a treasure-trove of scientific potential. It can now be used as a source of electric power. Urine-eating bacteria can create a strong enough current to power a cell phone. Medicines derived from urine can help treat infertility and fight symptoms of menopause. Stem cells harvested from urine have been reprogrammed into neurons and even used to grow human teeth.

For modern scientists, the golden liquid can be, well, liquid gold. But a quick look back in history shows that urine has always been important to scientific and industrial advancement, so much so that the ancient Romans not only sold pee collected from public urinals, but those who traded in urine had to pay a tax. So what about pee did preindustrial humans find so valuable? Here are a few examples…

Here’s a piece looking at the history of the WC – and it’s current impact:

The world needs more toilets – but not ones that flush

The invention of the flush toilet, or water closet, in 1596 ended open defecation and transferred excreta outside of homes for the first time. This was certainly a good thing in the short term, but today the flush toilet probably stands as one of the most unsustainable innovations in human history.

Think about it. Why would we want to increase the liquid volume of a potentially harmful substance – human waste? Most of the waste water that flush toilets create – more than 80% worldwide – ends up going directly back into the environment. No treatment, no use, just a lot of open sewers.

With the invention of flush toilets, the volume of waste created when humans go to the bathroom increased almost 20-fold. To deal with this new level of waste, we invented waste-water treatment plants. The aim of these sewage treatment systems has traditionally been to provide clean effluent that can be put back into the ecosystem.

The world needs more toilets – but not ones that flush

But we’ve been thinking of alternatives for some time – with this piece from 2007: