“Keep America Beautiful must rank as one of the most devastatingly effective PR campaigns of all time.”

.

Recycling is very much in the news, with companies not meeting expectations:

In fact, companies might not have to do too much anyway:

Although some companies are doing better than others:

The Body Shop launches ‘Return, Recycle and Repeat’ scheme across 225 stores – Packaging Europe

The question is, surely, whether it should be consumers and councils that should deal with all this packaging – or the manufacturers who produce it in the first place:

New recycling service for Pringles tubes and other similar containers – Exeter City Council News

These news pages have already asked this question:

Is the business of recycling just a fraud? – Vision Group for Sidmouth

Plastics and public relations – Vision Group for Sidmouth

For a bit of summer reading, here’s a reposting of parts of a piece from the Baffler, from a couple of years ago:

Lies, Damned Lies, and Recycling

Modern recycling was designed to deflect responsibility from the largest producers of waste

Matthew King, December 19, 2019

…

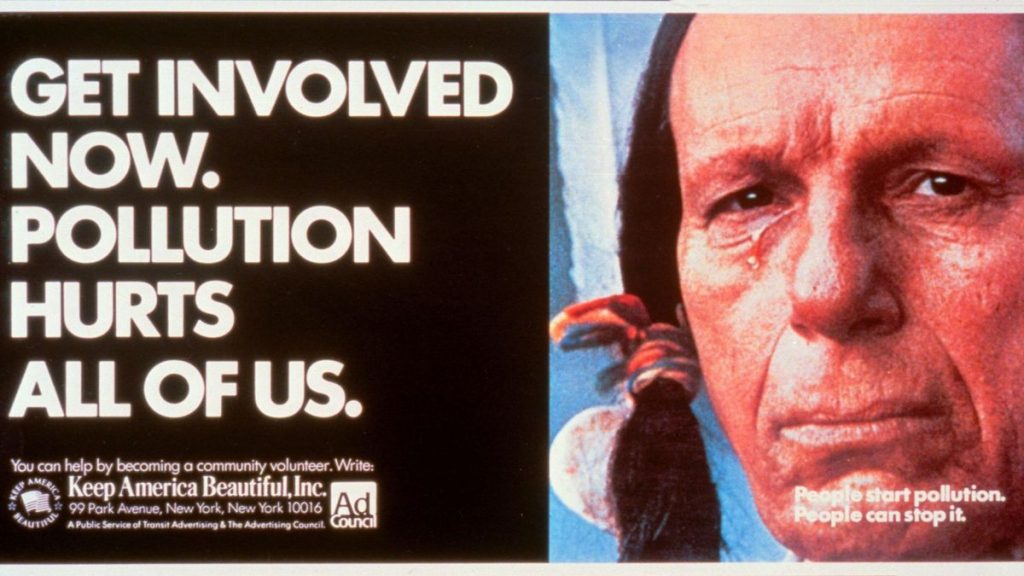

Modern recycling as we know it—the byzantine system of color-coded bins and asterisk-ridden instruction sheets about what is or isn’t “recyclable”—was conceived in a boardroom. The anti-litter campaigns of the 1950s, championed under the slogan of “Keep America Beautiful,” were funded by the producers of that litter, who sought to position recycling as a viable alternative to the sustainable packaging laws that had percolated in nearly two dozen states. In primetime commercials over the decades, American audiences met characters like Susan Spotless and “The Crying Indian” (played by Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti) who urged consumers to lead the charge against debris: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

Keep America Beautiful flaunted a fairy tale logic that demanded little from anyone. Landscapes would be rendered pristine as long as responsible citizens placed their garbage in the proper receptacle. Any unwanted items could be magically whisked away somewhere distant and unseen. In this fantasy world, polluted highways and parks were caused not by giant consumer brands who exclusively sold their goods in disposable packaging, or by raw material producers whose factories leaked toxic byproducts into rivers and lakes; the blame for environmental pollution was placed on the mythical hordes of careless individuals—“litterbugs”—who tossed food wrappers out of their car windows.

In one brazen swoop, the petrochemical industry disowned the blight of their products while sustaining highly profitable throwaway habits. Given how deeply this individualist message penetrated the national psyche, how thoroughly it deferred the prospect of producer-responsibility legislation for decades to come, Keep America Beautiful must rank as one of the most devastatingly effective PR campaigns of all time. And it was a tactic that American industry soon exported to the rest of the world.

…

The most damning legacy of Keep America Beautiful is not its evasion of corporate responsibility, or its sexist and racist mascots, but the way in which its message has curbed our ability to imagine alternative solutions to dealing with our waste. What was originally designed as a measure of last resort in the environmentalist credo—Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.—became the only realm of possible action. A white actor in redface shed a tear, and our problem was reduced to a fairy tale.

Mainstream pundits who view recycling as little more than a market to be recalibrated are hawking the same wrong-headed narrative. To the wonky technocrat, the future of recycling is another silicon-powered arms race: advanced recycling plants that resemble Amazon distribution centers; chirping orchestras of scanners, lasers, magnets, optical sensors, and AI robots that sort through thousands of items and material variants at light-speed. State-of-the-art recycling may be a poster-child for the neoliberal mindset, overcomplicating a problem in service of protecting existing industries and technologies. Rather than pursue the fool’s errand of perpetually rejiggering our recycling apparatus to fit the erratic packaging whims of consumer companies, how much easier would it be to solve this problem upstream, through firm legislation that standardizes the material byproducts that enter our waste streams to begin with?

With the prospect of more stringent, single-use bans on the horizon—led by the European Union, who has committed to sweeping plastic measures by 2021, and followed closely by North America and Asia—some global consumer brands are gesturing towards more holistic actions. A few of these initiatives are craven PR stunts, like limited-edition shoes and bottles made from recovered ocean plastic. Other projects mime genuine solutions, minus the urgency or commitment needed to actualize new ways of doing business.

Maybe the most ambitious effort so far has been a beta program called Loop, a waste-free delivery service that aims to revive the lapsed “milk man” model for recurring household purchases. If the service takes off, it could usher a meaningful change in consumer habits—though historically these sustainability experiments are the equivalent of exploratory committees, a vehicle for delaying actions or decisions while claiming to catalyze them.

More than any other resource, it is time we are wasting most belligerently. Half a century after American industry unleashed disposability on the planet, we’ve nearly passed the point of no return. Scarcity mindsets are anathema to the scores of rapidly industrializing countries who are following the Western playbook. Their waste footprints are expected to double (if not triple) by 2050, as global waste generation swells another 70 percent during that same time period. If we’re lucky, a fraction of this refuse will be diverted from landfills and incinerators. In her clear-eyed diagnosis of our looming epidemic, environmental scientist Dr. Max Liboiron compares recycling to “a Band–Aid on gangrene,” and our pretense of disposability a scorched-earth ideology that depends on “colonizer access to land.” Every faux-crisis about the death of recycling—all of which are really just news reports about the latest fluctuations in the global scrap market—should account for the fact that the system has been bankrupt from the beginning.

The best we can hope for recycling might be its ability to keep this modern failure top-of-mind. By pausing to consider the unseen costs of our rampant consumerism, we momentarily experience what Jørgensen calls “waste-mindedness,” which can facilitate our ability to slow down, question the virtues of growth, and recognize that no object is ever truly disposable. This is not meant to be a therapeutic or meditative sensation, but a rude awakening—one that journalist John Tierney tried to repress in his infamous 1996 polemic against recycling. His piece, entitled “Recycling Is Garbage,” argued there is no waste problem. Landfills are perfectly safe, with their double-layered clay and plastic lining. The world isn’t running out of raw materials or available dumping grounds anytime soon. His conclusion, which elicited a record amount of hate mail at the New York Times Magazine, followed that:

“Recycling does sometimes makes sense—for some materials in some places at some times. But the simplest and cheapest option is usually to bury garbage in an environmentally safe landfill. And since there’s no shortage of landfill space (the crisis of 1987 was a false alarm), there’s no reason to make recycling a legal or moral imperative. Mandatory recycling programs aren’t good for posterity. They offer mainly short-term benefits to a few groups—politicians, public relations consultants, environmental organizations, waste-handling corporations—while diverting money from genuine social and environmental problems. Recycling may be the most wasteful activity in modern America: a waste of time and money, a waste of human and natural resources.”

Tierney’s critique persuasively calls out the hypocrisy in how recycling has been sold to the public, the ways the liberal conscience falls prey to feel-good distractions, which are at best ineffectual and at worst counterproductive, even harmful. But then he sprints away from the problem, taking comfort in another false savior: the landfill. The article is a stunning time capsule of “end of history” optimism, channelled through a defense of modern garbage systems. More horrifying than Tierney’s hasty back-of-the-envelope calculations, or his free-market purity tests, is the utter lack of uncertainty about such a vast and unwieldy system. His voice channels the arrogance of some Malthusian scholar, brimming with blind faith about humanity’s ability to conjure ever-more clever ways of burying our waste out of sight and out of mind.

Certainly there are objects—now “garbage”—which humanity might have been better off not burying, let alone creating in the first place. Microplastics that have resurfaced in our food and drinking water. Nuclear waste and its half-life of thousands, millions, even billions of years. “Forever chemicals” that course through the blood streams of 99 percent of the U.S. population. Once inanimate materials are considered disposable, the mental leap to other things—animals, natural landscapes, entire communities of people—is not as far as we’d hope. More perilous than recycling’s ability to deflect responsibility is the way it seems to inflate our conception of what humanity can do, and undo—our potential to recover and defuse any harmful creations, to break things and put them back together, ad infinitum. If only.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Recycling | Matthew King