“the architecture of creative reuse”

The critical onus on architects and developers is to retrofit, reuse and reimagine our existing building stock, making use of the “embodied carbon” that has already been expended, rather than contributing to escalating emissions with further demolition and new construction.

.

Yes, we can recycle stuff – but we can also reuse stuff:

When is a ‘dump’ not a ‘dump’: when it is a ‘reuse centre’ – Vision Group for Sidmouth

Why throw things away if they can be repaired and reused?

Sarah Allen of Exmouth suggests… we reuse stuff! – Vision Group for Sidmouth

And this same ethos can also extend to our built environment:

Urban mining: recycling buildings – Vision Group for Sidmouth

RetroFirst: “the greenest building is the one that already exists” – Vision Group for Sidmouth

Here’s a great example of this – which begins at an incredibly resourceful (in every sense of the word) ‘recycling’ centre in Japan – as told by Oliver Waitwright of the Guardian:

‘Demolition is an act of violence’: the architects reworking buildings instead of tearing them down

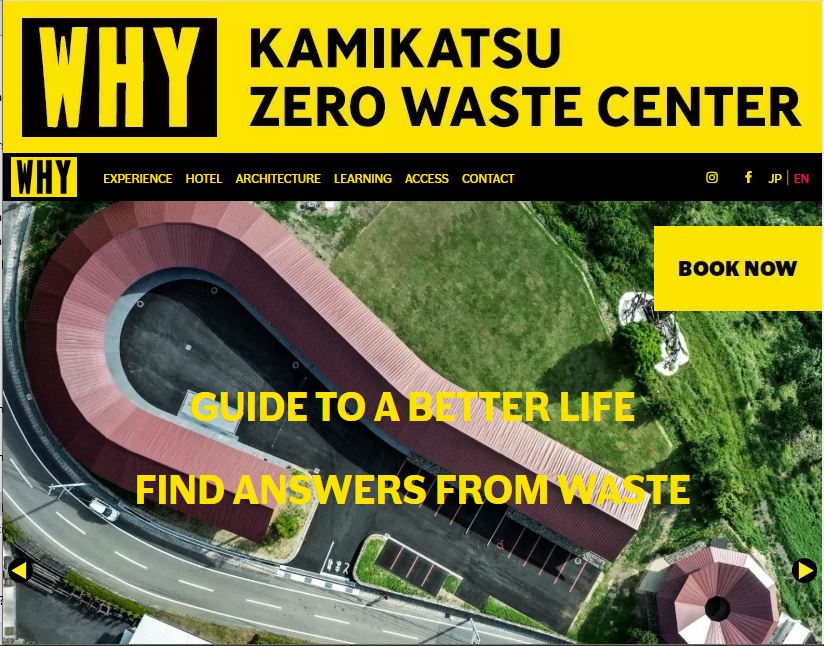

Nestled like a red question mark in the hills of rural Japan, the Kamikatsu Zero Waste Centre is a recycling facility like no other. A chunky frame of unprocessed cedar logs from the nearby forest supports a long snaking canopy, sheltering walls made of a patchwork quilt of 700 old windows and doors, reclaimed from buildings in the village. Inside, rows of shiitake mushroom crates donated by a local farm serve as shelving units, while the floors are covered with cast terrazzo made from broken pottery, waste floor tiles and bits of recycled glass, forming a polished nougat of trash.

It is a fitting form for what is something of a temple to recycling. In 2003, Kamikatsu became the first place in Japan to pass a zero-waste declaration, after the municipality was forced to close its polluting waste incinerator. Since then, the remote village (with a population of 1,500, one hour’s drive from the nearest city) has become an unlikely leader in the battle against landfill and incineration. Residents now sort their rubbish into 45 different categories – separating white paper from newspapers, aluminium coated paper from cardboard tubes and bottles from their caps – leading to a recycling rate of 80%, compared with Japan’s national average of 20%. Villagers typically visit the centre once or twice a week, which has been designed with public spaces and meeting rooms, making it a social hub for the dispersed town. It even has its own recycling-themed boutique hotel attached, called WHY – which might well be your first response when someone suggests staying next to a trash depot…

The project is one of many such poetic places featured in Building for Change, a new book about the architecture of creative reuse. Written by the architect and teacher Ruth Lang, it takes in a global sweep of recent projects that make the most of what is already there, whether breathing life into outmoded structures, creating new buildings from salvaged components or designing with eventual dismantling in mind. The timing couldn’t be more urgent. As Lang notes, 80% of the buildings projected to exist in 2050, the year of the UN’s net zero carbon emissions target, have already been built. The critical onus on architects and developers, therefore, is to retrofit, reuse and reimagine our existing building stock, making use of the “embodied carbon” that has already been expended, rather than contributing to escalating emissions with further demolition and new construction.

While the urgency of the issue has been occupying the industry for some time – the Architects’ Journal leading the way with its RetroFirst campaign – the topic recently made national headlines when Michael Gove, then communities secretary, ordered a public inquiry into the proposed demolition of the 1929 Marks & Spencer flagship store on Oxford Street. Whereas heritage conservation would once have been the primary reason to retain such a building, the conservation of the planet has now taken centre stage. Campaigners argue the development proposals would release 40,000 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere, whereas a low-carbon “deep retrofit” is eminently possible instead. They point to examples such as the former Debenhams in Manchester, a 1930s building which is being refurbished and extended. To put the scale of the emissions in context, Westminster city council is currently spending £13m to retrofit all of its buildings, to save 1,700 tonnes of carbon every year; the M&S demolition proposal alone would effectively undo 23 years of the council’s carbon savings...